He is De Niro’s Johnny Boy: violent, impulsive, doomed (and, frankly, dumber than a bag of rocks). But Kassovitz has actually borrowed Vinz from a different Scorsese movie- Mean Streets, not Taxi Driver. Early on, we see him doing the well-worn Travis Bickle shtick-”You talkin’ to me?”-in front of his bathroom mirror. Saïd is the closest thing to the movie’s eyes, whereas Vinz is its motor, its causal force, and Cassel is an impressive athlete of an actor. It’s an odd choice, emphasizing how little happens to these guys on a day when so much happens to them. One minute the trio are running from police, or being hassled by the police, or being tortured by the police, the next they are sitting around telling lame jokes and bragging about getting laid. The time flashes across the screen at random intervals: 10:38, 12:43, 14:12.

Still, Kassovitz presents the day’s heightened agitation against a template of boredom and aimlessness. It would be as uneventful as any other day, except that the near-fatal police beating of a youth has sparked a minor uprising in the projects. formats) observes the multiethnic trio of Jewish Vinz (Vincent Cassel), North African Saïd (Saïd Taghmaoui), and West African Hubert (Hubert Koundré) over a single day. La Haine (which is available on DVD only in French and U.K.

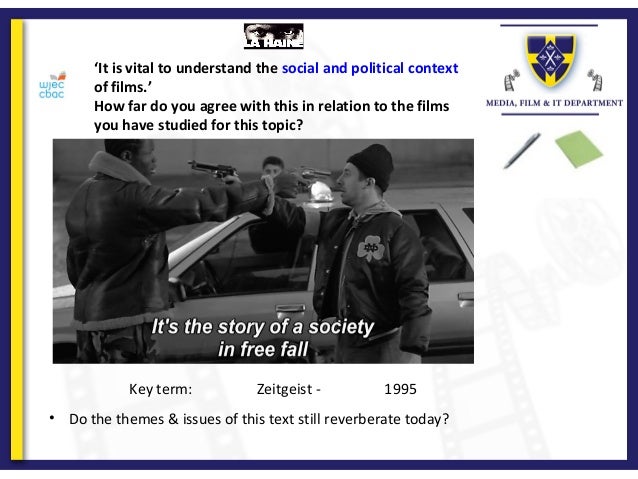

“Funny,” the young rioters seem to be saying, “but I don’t feel French.”īut it’s hard to decide how much La Haine’s value as prophecy elevates Kassovitz’s film, because otherwise-though it caused a sensation in France when it first came out and became an unexpected box office hit there -it isn’t very good. The French government insists that the inhabitants of these ghettoes are “citizens,” as French as anyone, but it lacks either the will or the means to integrate them into the everyday civic and economic life of the nation. And it’s not a bad metaphor for France’s willful blindness to the problems of its suburban ghettos, where immigrants from North and sub-Saharan Africa (and now their children and grandchildren) are garrisoned outside France’s beautiful old cities, literally marginalized. It’s a little didactic, but it’s only a joke. Mathieu Kassovitz’s acclaimed 1995 film La Haine (Hate), which examines the lives of three young men from a housing project outside Paris, begins with its narrator telling the old joke about a guy who, falling from a tall building, repeats to himself, “So far so good … so far so good.” The joke refers to the explosive conditions that were building in France’s suburban housing projects at the time.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)